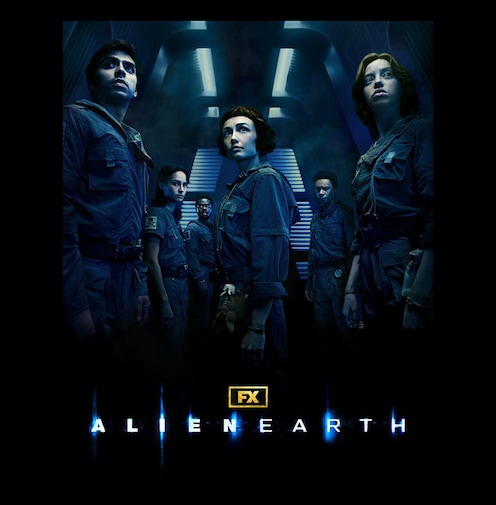

FX's Alien: Earth | Watch on Hulu

Fear takes new forms.

94%

85

Explore Episodes

BEHIND THE SCENES

The Making of Alien: Earth

Watch exclusive videos of the making of Alien: Earth

HIGH-RESOLUTION GALLERIES

Alien: Earth Galleries

View the Alien: Earth Episodic Galleries

HIGH-RESOLUTION GALLERY

Alien: Earth Official Key Art

Characters